Creating High-Performance Afterschool Programs

By Sonia Toledo

In more than 25 years of training afterschool directors in New York City, I have learned that one of the greatest challenges supervisors face is developing and retaining their staff. I spend most of my energy researching best practices for afterschool and figuring out how to educate directors and make the research applicable to their work. One of the most consistent complaints I have heard is high staff turnover. Site supervisors are in a continuous struggle to develop and train new employees on the fundamental skills—managing groups, dealing with disruptive behavior, and so on—that youth workers need before they can successfully implement learning activities.

In more than 25 years of training afterschool directors in New York City, I have learned that one of the greatest challenges supervisors face is developing and retaining their staff. I spend most of my energy researching best practices for afterschool and figuring out how to educate directors and make the research applicable to their work. One of the most consistent complaints I have heard is high staff turnover. Site supervisors are in a continuous struggle to develop and train new employees on the fundamental skills—managing groups, dealing with disruptive behavior, and so on—that youth workers need before they can successfully implement learning activities.

One way to break this cycle of continual onboarding is to support site supervisors in implementing processes to build a high-performance culture in their afterschool programs. The intention is to build a culture in which staff collaborate and learn together to reach program goals. Building a culture where staff feel heard and have opportunities to develop skills may improve the retention rate.

The idea of high-performance cultures comes from the corporate world, which may have something to teach us about stabilizing the out-of-school time workforce. One precept is that long-term success derives from an organization’s capability to be consistent in delivering services to its clients (Kaliprasad, 2006). In afterschool programs, our clients are our children and youth. Kaliprasad (2006) cites major disadvantages that can keep an organization from performing at a high capacity, including (1) misalignment between staff capabilities and the skills required to deliver quality service and (2) unclear organizational systems and processes. To transform afterschool programs into highperforming cultures, we need to address these challenges. This essay recommends a model, borrowed from the corporate sector, for building a high-performance culture in afterschool programs at the site level. If implemented with fidelity, this model can support afterschool programs in stabilizing their workforce, improving their performance, and delivering quality services to children and youth.

Challenging Workforce

The challenges to building a high-performance culture in an afterschool program generally are related to the transient workforce. Afterschool programs typically hire community residents and college students as frontline staff to work directly with children. Most positions are part-time; the pay is usually on the borderline of minimum wage. These characteristics lead to the high staff turnover and inconsistent service delivery that plague our field (Baldwin & Wilder, 2014).

According to a survey done by National AfterSchool Association (NAA, 2006), one-third of youth workers are between 18 and 30 years old. Their stage in life contributes to staff turnover, because young adults typically are still in school themselves or are figuring out their own career paths. Furthermore, many are part-time workers, who generally transition out of afterschool work in two or three years (NAA, 2006).

Staff levels of education can also be a challenge to consistency in the afterschool workforce. Although supervisors often hold associate’s or bachelor’s degrees, the degrees may be in fields that are not relevant to work with children (NAA, 2006). Therefore, training and development become critical factors in building a high-performance culture for site supervisors and direct service staff.

Four Components of a High-Performance Culture

A field like ours that is still establishing its role in society needs strong systems to support growth and sustainability. Bradshaw (2015) emphasizes that afterschool program leaders usually understand the necessity of developing their workforce, but they often fail to connect the intention with actual implementation. Investment in middle managers is critical; in the long term, the site supervisors are the ones who will implement, reinforce, evaluate, and enhance program practices (Bradshaw, 2015). They are the ones who can form a high-performance culture at the site level.

One model for a high-performance culture that can easily be adopted by afterschool programs was proposed by M. J. Wriston in 2007. Wriston’s model emphasizes four components:

- Creating a collaborative climate

- Building a culture of accountability

- Focusing on outcomes

- Having robust processes

This model can support supervisors in establishing a learning culture that benefits both staff and program participants. With its emphasis on learning as a team and building systems, it can help staff stay focused on youth and program outcomes.

Creating a Collaborative Climate

According to Wriston (2007), organizations and teams must understand the power of collaboration at every level to raise the energy of their creative activity and problem solving. Collaboration brings value to workers’ actions in the workplace. To begin, afterschool leaders should have a clear process to create a shared learning culture that continuously builds the capacity of program staff to achieve the program’s vision and intended outcomes. Processes should be in place to have staff learn and create together on a regular basis. Programs can train staff as a team so they learn consistent methods and strategies.

Staff might also meet on a regular basis to design curriculum that supports the program’s focus. Baldwin and Wilder (2014) point out that afterschool staff who feel valued for their work are invested in doing their best. Creating an environment where staff members have input on curriculum design and work together to resolve day-to-day issues can create that sense of value and purpose. Together, staff can co-create a shared vision of the participant outcomes they are working toward. According to Wriston (2007), organizations that establish a collaborative process for team learning will benefit by establishing great synergy and a clear competitive edge for their services.

A starting point for site supervisors looking to create a collaborative climate is to bring staff into the process of writing procedures. Usually, site procedures are handed to staff, who are expected simply to implement them—though the staff are the ones who know best what Toledo CREATING HIGH-PERFORMANCE AFTERSCHOOL PROGRAMS 31 procedures do and don’t work. Instead, try writing a new procedure and then ask staff for feedback on how to strengthen it. Remind them, as necessary, that procedures are action steps to fulfill written policies. When you and staff members have revised the draft together, set up a trial period to test the new procedure and again ask staff for feedback. Bringing staff into the process of creating procedures on an ongoing basis will give them ownership of program operations. The goal is to create a culture in which everyone has input. Remember to give staff time to prepare during their allotted hours, or else incorporate time for this work into regular staff meetings. Finding ways to facilitate a collaborative climate may seem difficult at first, but it will benefit staff morale in the long run.

Focus on the Outcomes

As afterschool programs are being held accountable for academic outcomes, identifying clear goals is becoming ever more crucial. Staff can’t easily stay focused on outcomes that have not been clearly identified! As Wriston (2007) explains, highperformance organizations are clear about expectations at all levels; they continually emphasize their priorities to keep staff motivated.

Though afterschool programs often tend to focus on many areas, they are more likely to experience success when they focus on key areas that support their specialty, whether that is literacy, a sport, or STEAM (science, technology, engineering, and math, plus arts). In addition to specific academic or specialty content areas, programs often have social and emotional developmental goals, such as fostering team skills or self-efficacy. Most social and emotional outcomes support the learning environment of the classroom. For example, teaching children how to work as a team can support effective STEAM activities. Help your staff prioritize building a strong classroom culture while focusing on your program’s specialty skills. One solution is to build outcomes on top of one another. Identifying the specific outcomes and prioritizing them for each activity— whether those outcomes are academic, developmental, or focused on the program’s specialty area—will support the staff in facilitating learning activities.

The best approach is to break down the developmental, specialty, and academic outcomes to help staff facilitate outcomes-focused activities. You can begin by creating goals that are relevant to the challenges your staff is facing. Make them short-term goals that can be accomplished within two to three months, so your team can experience success and feel motivated to take on another challenge. Choose one area at a time; the team can measure, for example, youth engagement, reduction of negative behaviors, or percentage of homework completed. Make it a creative process to encourage problem solving among your staff.

Culture of Accountability

As funders and policymakers are holding afterschool programs accountable, so programs can also create accountability systems for their employees. A culture of accountability supports a team by building consistency in expectations, recognition, and reinforcement of performance; it also fosters willingness to address any corrections necessary to get back to alignment with expectations (Wriston, 2007).

Holding leadership and staff accountable is not that complicated, according to Edmonds (2010); implemented consistently, accountability heightens an organization’s credibility. Edmonds (2010) outlines two simple steps leaders can take to reinforce accountability among their staff: (1) conduct proactive observations regularly in all areas of the program and (2) implement a consequence management system. Afterschool programs leadership can easily implement these two steps to hold their staffs accountable by using standards to stay focused on the intended outcome and by providing support systems to build staff members’ capacity if needed. Standards can support organizations in aligning with their goals (Kaliprasad, 2006) and holding their staffs accountable for the delivery of service (Cole, 2011). You can adopt the child and youth developmental standards from the Council on Accreditation (2018) or standards adopted by your state, if any. Standards give you benchmarks to measure progress in all program areas.

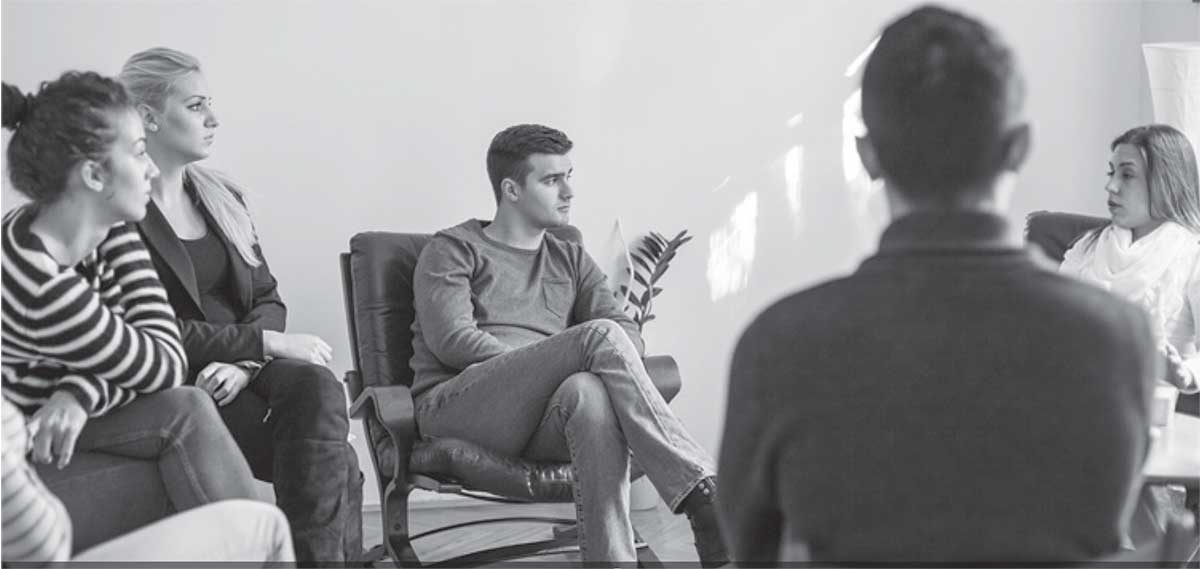

One way site supervisors can begin to build a culture of accountability is holding daily huddles or weekly check-ins. Meetings should be short and to the point. Bring two to three questions, based on the goals you have You can begin by creating goals that are relevant to the challenges your staff is facing. Make them short-term goals that can be accomplished within two to three months, so your team can experience success and feel motivated to take on another challenge. 32 Afterschool Matters, 28 Fall 2018 set with staff, and ask everyone to give a quick response. Such check-ins promote team work and accountability. Regular observations are another way to build accountability. Staff can rotate to conduct observations in short 20-minute sessions. Make sure to use established standards to reflect on what you are observing. When huddles and observation become routine processes, staff will be empowered to do their very best.

Robust Processes

Staff turnover can make it difficult for afterschool programs to create and sustain robust processes. However, organizations that create a high-performance culture will reduce turnover because staff will be more invested in their jobs (Wriston, 2007). In afterschool programs, the key processes are the ones we use with participants, so that all staff deliver activities consistently. Processes that are clear and simple give staff a structure to follow but still leave room for creativity and autonomy. Wriston (2007) states that strong processes can increase staff effectiveness. When afterschool staff have a process to follow in facilitating activities, they can feel confident that they are addressing children’s needs and contributing to intended outcomes.

One main role of the site supervisor in facilitating robust processes is professional development. It’s easy to fall into the expectation that staff know how to, for example, facilitate art activities because they are artists. But having a step-by-step process for facilitating activities or managing behavior can help staff to feel confident and enable them to connect theory with practice. Once they have experienced success with the process, they will feel self-confident enough to create their own processes to meet the unique needs of their particular groups of children.

One common way to teach instructional processes is to engage staff in the processes as program participants will experience them. For example, you could teach your staff the 1-3-6 protocol (Teaching Channel, 2018) for building literacy and creativity by taking them through the process yourself. First, introduce a text—for children, an age-appropriate book or video; for staff, perhaps a professional article. Then go through the 1-3-6 process.

1: Individuals freewrite for two or three minutes. (Little ones can draw.)

3: In groups of three, participants share their reflections and come up with three ideas that are similar or overlapping. They also note vocabulary words and topics to explore further.

6: Two groups of three form a group of six. Participants create a presentation that brings their reflections into tangible form, such as a mural, book, or presentation. The complexity of the project depends on the amount of time devoted to the protocol.

If you can have staff practice this process, perhaps more than once with different learning topics, they will gain confidence. Then they can implement the process with their groups. Once they feel confident with the 1-3-6 protocol, you can add another process.

Reflection

Afterschool programs can create strong high-performance cultures if they commit to processes that build staff members’ abilities. Using Wriston’s (2007) four-step model can help afterschool programs to achieve clear outcomes and, ultimately, gain more funding opportunities. To encourage staff to stay for two, four, or more years, afterschool programs must create a culture of collaboration and stay focused on their intention in delivering services. Then they can expect to see clear evidence of growth in children and youth.

Creating raving fans for afterschool programming begins with staff. Staff who are raving fans turn children and youth into raving fans who show up every day and achieve the outcomes for which the program is designed. Holding people accountable is necessary for momentum in the right direction—and allowing staff to feel they are part of creating goals will encourage them to feel more invested.

We need to shift perspective to realize that we are hiring not just employees but a generation of leaders and creators who will influence children and youth into the future. Developing youth workers for their worth, not just their duties, may create opportunities for our programs and our youth that we have not witnessed before.

founded Dignity of Children in 2008 to create environments where children can thrive. As CEO, she continues to support directors in establishing strong learning cultures to build quality environments. Sonia is pursuing her PhD in education and global training and development from North Central University. She completed NIOST’s Afterschool Matters Practitioner Research Fellowship in 2017.

Sonia Toledo VOICES

For references, see PDF

Tags: Workforce Development, Professional Development, Best Practices, Outcomes, Assessment, Program Quality