Supporting Effective Youth Work: Job-Embedded Professional Development in OST

By Jocelyn S. Wiedow

Youth work practitioners play a critical role in providing high-quality out-of-school time (OST) opportunities. Research shows that high-quality programs contribute to positive outcomes for youth (National Institute on Out-of-School Time, 2009). Beyond research, practitioners tell stories that reflect how youth worker quality affects youth experience, both positively and negatively.

Youth work practitioners play a critical role in providing high-quality out-of-school time (OST) opportunities. Research shows that high-quality programs contribute to positive outcomes for youth (National Institute on Out-of-School Time, 2009). Beyond research, practitioners tell stories that reflect how youth worker quality affects youth experience, both positively and negatively.

Unfortunately, quality professional development is not always available to youth-serving organizations—and it isn’t always a priority. The key to creating and sustaining quality is supporting the development not only of youth but also of staff (Sabo Flores, n.d.).

Challenges to developing staff quality include limited staff hours and lack of funding for training. However, even organizations that have enough time and money still may not develop their people effectively. Traditionally, organizations send staff to trainings without offering follow-up support to enable them to apply the learning (Hirsh, 2009; National Staff Development Council, 2001; Senge, 1990). To effectively develop youth worker expertise, supervisors must create a culture that allows staff to integrate their learning into practice and reflect on its application. This article outlines how supervisors can create a culture of learning by employing job-embedded professional development. It offers three models for staff learning, each supported by practical tips and real-world examples.

Creating a Culture of Learning

Supervisors—whether they are directors, managers, or coordinators, whether they have responsibility for one site or many—are responsible for the effectiveness of staff and programming. If they are supported by the organization’s top leaders, they can create conditions that enable staff to grow as a team and as individuals. A culture of learning encourages employees to increase their knowledge and abilities and to function more productively—even when team members have a wide range of skills and experience. Personal growth is important even for the most seasoned staff members.

Challenges to developing staff quality include limited Supervisors can encourage this discipline by establishing continuous improvement as a norm. Continuous improvement involves ongoing development, beyond specific training days, with opportunities to practice and reflect on new skills. It encourages experimentation, supporting staff over time to try new strategies rather than subjecting them to immediate evaluation (National Staff Development Council, 2001).

Challenges to developing staff quality include limited A culture of learning and continuous improvement has many benefits. Organizations grow stronger when they commit to the personal growth of employees (Senge, 1990). Senge (1990) notes that individuals who are supported in their personal growth are committed to their work, take initiative, and learn quickly. Some OST practitioners come to work with this mindset; others need support to develop it. Staff whose supervisors support their learning and give them voice in decision-making are more likely to continue working with youth. When support is inadequate, staff turnover is higher, requiring supervisors to hire and train new staff continually (Hartje, Evans, Killian, & Brown, 2008). Supporting staff development is therefore a cost-effective choice for organizations.

OST-Style Support for OST Staff

For OST providers, helping staff grow should be easy. It is what we do every day with young people. In a study of five high-quality youth programs, a common feature emerged: These programs developed into learning organizations by incorporating positive youth development strategies with staff (Sabo Flores, n.d.). Like effective youth developers, successful OST staff developers:

- Put learners at the center. Strategies for strengthening the learning both of young people and of staff include participation, engagement, discovery, and critical reflection (Huebner, Walker, & McFarland, 2003). One common tactic is to model youth development best practices in staff training.

- Lead as facilitators of learning, not as experts. Youth and youth workers both bring their own perspectives and prior knowledge; both can learn more when they share learning with others (Madzey-Akale & Walker, 2000). Supervisors should create space for staff to exchange ideas and knowledge. One model is formal or informal mentoring, in which staff members demonstrate specific skills for each other.

- Incorporate reflective practices. Youth workers incorporate reflection as a way to help youth better understand what they are learning and how it relates to their experience. Similarly, access to published research, combined with reflection, enables staff to connect their practice to theory (Huebner et al., 2003).

Elements of Job-Embedded Professional Development

Job-embedded professional development is a way to apply OST best practices to support staff. Its key elements set the conditions for a culture of learning grounded in continuous improvement. Organizations that successfully embed professional development:

- Incorporate learning in all job descriptions. Organizations are more successful when the expectation of continuous learning is embedded in job descriptions (Croft, Coggshall, Dolan, Powers, & Killion, 2010). Connecting development to key job functions at hiring not only sets up expectations but also demonstrates the organization’s investment in staff.

- Allot time, space, structures, and supports (Croft et al., 2010; National Staff Development Council, 2001). Dedicating time and resources so staff can integrate theory and practice is a vital investment (Huebner et al., 2003). One way to find time in already tight schedules, explored in detail below, is to incorporate new practices into existing staff meetings.

- Pay staff to learn. Job-embedded professional development is, by definition, integrated into the paid workday. The fact that this definition is a barrier for many organizations is a strong argument for writing staff development into funding requests. Holding staff and programs accountable for positive youth outcomes means that organizations have to be accountable for building staff skills (Surr, 2012).

- Connect staff learning to youth experience. Job-embedded learning is closely linked to the work environment (Croft et al., 2010). Lessons learned in professional development must be brought back to the work staff do with youth.

These powerful directives set a foundation for changing the culture of an organization. They can help supervisors determine what professional development processes to implement.

Process of Job-Embedded Professional Development

Professional development has two main elements: content and process. Content covers the things staff need to learn, whether organization-specific practices or topics in youth development. This article focuses on the processes supervisors can use to connect content with practice. Sabo Flores (n.d.), in her study of five high-quality programs, emphasized the importance of process in staff development.

The value of the approach taken by these five out-of-school-time organizations lies not so much in what the staff members create … but in the processes by which they create…. It is not only the quality of the curricula and activities, but the process of developing the curricula and activities. It is not only the number and type of professional development activities available, but the ways in which the organization relates to staff members as learners and supports them to grow and learn. the curricula and activities. It is not only the number and type of professional development activities available, but the ways in which the organization relates to staff members as learners and supports them to grow and learn.

Organizations that implement the first three elements of job-embedded professional development outlined above but do not connect the learning to experience are not fully supporting their staff. The process of job-embedded professional development enables staff to integrate content into their work. Even when staff attend outside trainings, they need time to reflect on and adjust their practices. The process enhances the content—just as when we create space for young people to connect their learning to their experience.

A Place to Start

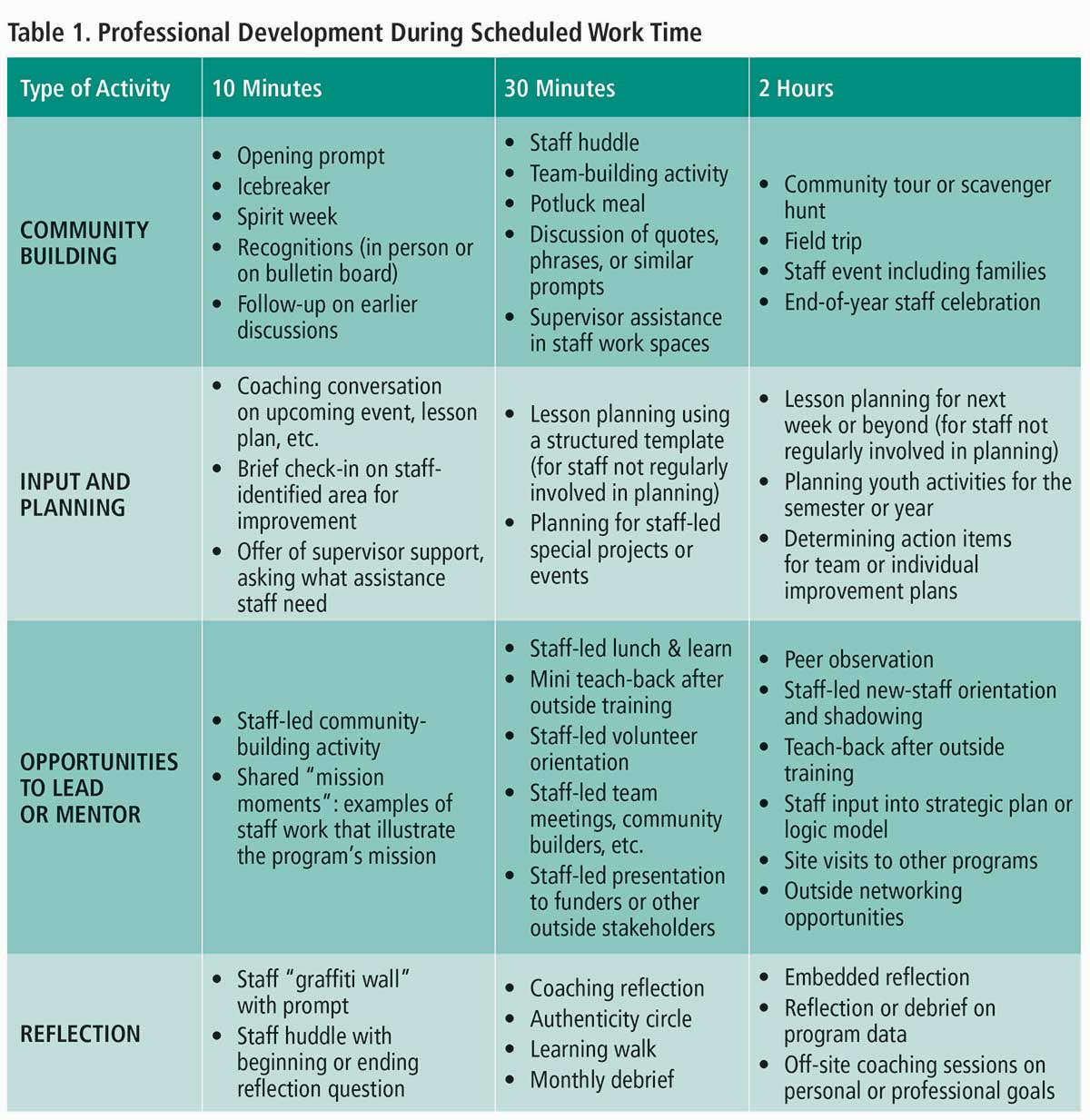

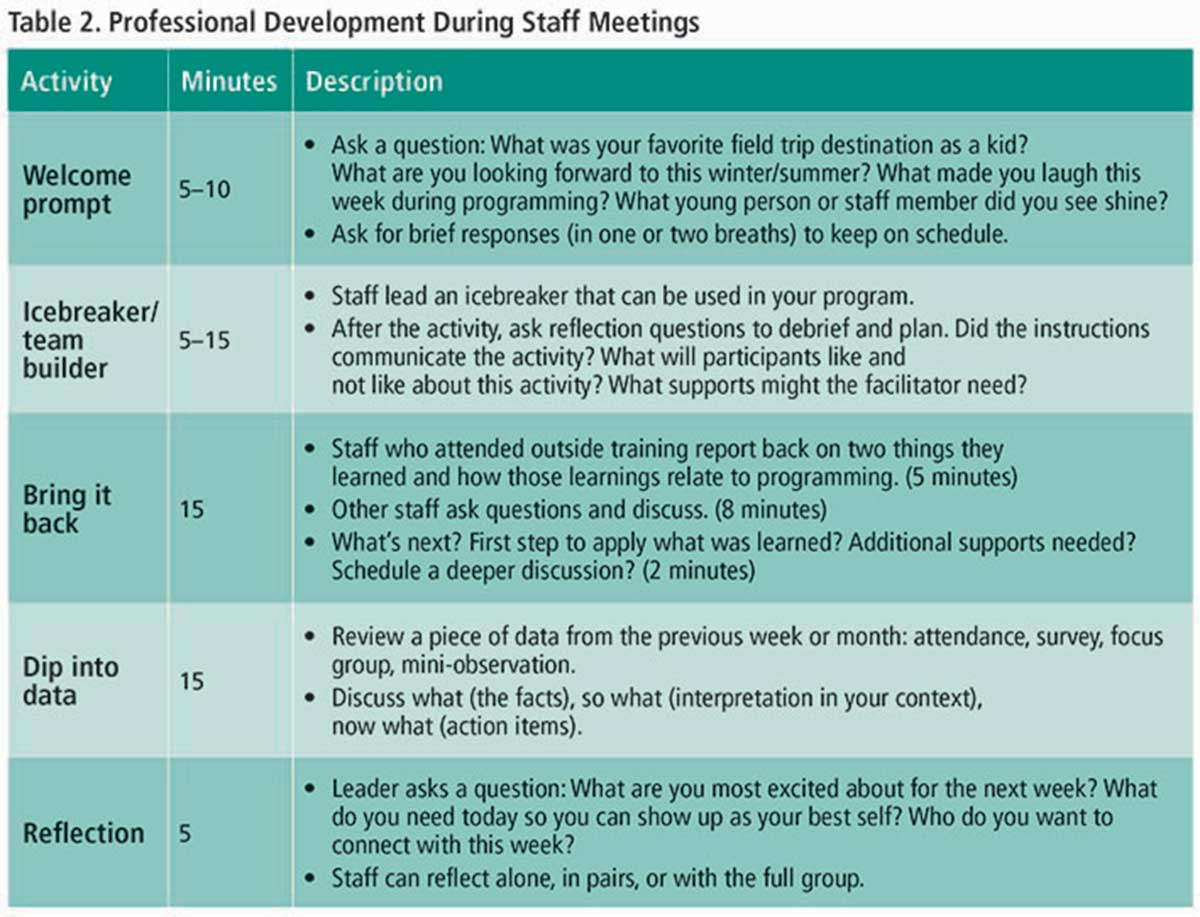

Embedding professional development into the workday can feel overwhelming. One place for supervisors to start is to look at what the program is already doing well and what they know from their youth work practice. Table 1 (page 21) shows four elements of quality youth programming and provides examples of professional development activities supervisors can lead in each of those areas if they have 10 minutes, 30 minutes, or two hours. Some activities are stand-alone, while others can be added to an existing agenda. Any of them can move regularly scheduled staff meetings beyond updates and logistics to provide meaningful learning opportunities.

Table 2 offers detailed examples of staff development activities that can be integrated into regularly scheduled staff meetings, one or two at a time. To build leadership, rotate staff members to facilitate different parts of the agenda

Three Job-Embedded Professional Development Strategies

The strategies for job-embedded professional development outlined here are just three of many. Coaching, professional learning communities, and peer observation can be used independently or combined. All three can be scaled to fit the structure and complexity of the program or organization. Real-world examples of how each strategy can work come from programs in Saint Paul, Minnesota, that participate in the Sprockets network.

Coaching

One way for busy supervisors to be intentional in engaging staff in professional development is to provide coaching. Coaching is an individualized approach that empowers staff members to become “self-directed persons with the cognitive capacity for excellence both independently and as members of a community” (Costa & Garmston, 2003).

How It Works

Coaching can be a process of engaging staff in thoughtful examination and transformation of their thinking about their work. High-quality coaching depends on four main components:

- Creating a safe environment. Trust is the foundation of a successful coaching relationship. Staff may feel vulnerable about sharing their struggles with their work.

- Asking good questions. Thoughtful open-ended questions are a catalyst of critical thinking. Good questions allow staff to reflect on their plans and implementation; they also prompt self-evaluation.

- Listening with intensity. Coaches need to be aware of both verbal and nonverbal communication. They must listen for understanding, ask for clarification when necessary, and paraphrase what they hear.

- Providing objective feedback. When coaches share what they have seen and heard, they enable staff to reflect and make their own decisions, informed by data.

These four components can increase the effectiveness of an intentional coaching practice. Coaching isn’t just making time to talk; it is facilitated conversation in a safe environment. That said, coaching interactions should be adjusted to meet staff needs. Sometimes supervisors may need to transition a coaching conversation to a problem-solving or planning conversation, all the while maintaining the intent of meeting the staffer’s self-directed learning needs. Coaches must be flexible.

Besides offering structured coaching, supervisors can also look for ways to integrate coaching informally in regular staff interactions, such as during planning meetings or program time. As an organization embeds professional development in its practice, coaching can be applied to everyday interactions across roles—whether staff are working together, engaging youth, or supporting families. In every case, the learning needs of the individual being coached direct the conversations.

The role of coach does not have to fall on the supervisor alone. Every staff person has the capacity to be a coach at specific times. When leaders make the four components of coaching common practice, staff members can coach their peers. After all, they already serve as coaches to program participants and families.

Costa and Garmston (2003) reviewed numerous studies that showed the benefits of coaching. When coaches build trust, create space for reflection, and empower autonomy, staff members can build self-efficacy, with the ability to self-manage, self-monitor, and self-modify (Costa & Garmston, 2003). Staff who receive coaching can improve their confidence and ability to work independently instead of needing to be told what to do. For organizations, benefits included a more professional work culture, higher job satisfaction, and increased collaboration. Most importantly, coaching was associated with increased positive outcomes for young people (Costa & Garmston, 2003). Coaching also benefits the coach. For many practitioners, the reason they got into youth work is lost when they become supervisors. Being a coach taps into their primary areas of expertise—listening, building trust, fostering learning—and can renew their sense of fulfillment as they engage others in growth and development.

Supervisor Best Practices

A first step for supervisors interested in coaching staff is to get training. Our system uses resources from the David P. Weikart Center for Youth Development (n.d.), which For organizations, benefits included a more professional work culture, higher job satisfaction, and increased collaboration. Most importantly, coaching was associated with increased positive outcomes for young people provides a full-day quality coaching training as part of its Youth Program Quality Intervention. Other training options may come from the school district, the state department of education, a local college, or a third party (Hanover Research, 2012). Coaching is most effective when it starts with the supervisor, even if peer coaching is an eventual goal. Leaders must first model best practices and demonstrate their commitment. The budget has to include regular staff time for coaching.

The frequency of coaching meetings can range, based on the context. Are there changes in programming or staff? Have new goals or priorities been set? Such changes will go more smoothly if supported by professional development. When it’s time to add peer coaching to the mix, supervisors can coach staff to become coaches, demonstrate coaching skills during staff meetings, or encourage formal training, if that option is available.

From the Field

The mission of Saint Paul Urban Tennis (SPUT) is “transforming lives through tennis.” Although SPUT operates year-round with a small full-time staff, its summer programming increases dramatically, incorporating a large number of high school and college-age tennis coaches at sites across Saint Paul. A few summer coordinators are hired to support clusters of tennis sites. Because these summer coordinators have limited access to the training that full-time staff attend during the school year, SPUT leaders had to figure out a realistic way for them to learn reflective coaching skills. The solution was a brief training that shows coordinators how to use a SPUT-designed reflective conversation form with tennis coaches. They can use this form to reflect with tennis coaches during site visits or at trainings where lead tennis coaches meet with their coordinator. The form includes four questions for observation and reflection:

- How did it go?

- What went well? What made that successful?

- What would you do differently?

- What support do you need?

The form also includes prompts for the coordinator to reflect with the tennis coaches on their strengths and opportunities for improvement.

This process of empowering coordinators to coach summer tennis coaches has not only improved the quality of programming but also helped build positive experiences for the young staff. Laura Fedock, associate director of SPUT, summarized the effect this way:

The reflective conversation form has helped coordinators build community by creating the space to connect with tennis coaches in a meaningful way. Our coaches learn that SPUT cares about helping them build their skills and about equipping them to do well in their job. Feeling supported in their work has benefited SPUT, as many coaches return for summer jobs year after year. (personal communication, May 8, 2018)

Professional Learning Communities

Where coaching supports individual growth, professional learning communities (PLCs) allow staff members to learn collaboratively (Hirsh, 2009). PLCs share a common focus so that staff can learn together, tapping the range of experience, knowledge, and abilities present in almost any OST program. PLCs can be formed at multiple levels within an organization or among many organizations (National Staff Development Council, 2001). This section focuses on PLCs within individual organizations and supervisors’ role in creating them.

PLCs provide a nonjudgmental network for personal and professional support. According to Hanover Research (2012), they support:

- Teamwork and collaboration through discussion of dilemmas and possible solutions

- Professional growth through sharing of knowledge and experiences, reflection on practices, setting of goals for growth, and constructive feedback

- Leadership skills through interaction with colleagues

- Productivity through building of staff relationships

- Buy-in for vision and practices through engagement in the group process

Depending on their size and the structure and context of their work, different OST organizations might choose different PLC models. Three models are outlined here.

Authenticity circles. A merger of coaching and collaborative learning, an authenticity circle is a small group of colleagues who come together for peer coaching connected to real dilemmas. At each meeting, one individual presents a dilemma. The colleagues practice coaching skills to help determine possible solutions. Authenticity circles can be helpful for staff teams at one site or for supervisors across multiple sites. Brown-bag meetings. These informal meetings are called “brown bag” because they occur during lunch—paid lunch time, in keeping with the principles of job-embedded professional development. Frequency can range from weekly to monthly to quarterly. One 24 Afterschool Matters, 28 Fall 2018 Wiedow SUPPORTING EFFECTIVE YOUTH WORK 25 approach is to have staff members sign up to facilitate discussion on a topic they want to present. Staff could generate a list of topics to cover during the program year, or supervisors can bring strategic topics based on program or community needs. Informal lunch meetings are ideal for fostering peer learning and for creating safe places where staff can practice presentation skills. Learning cohort. Typically seen as more formal, learning cohorts are groups of staff from different departments, sites, or organizations who learn together over a set period. Cohorts allow participants to learn together and build deep understanding on a shared topic of interest. Groups can decide how they want to learn together.

Supervisor Best Practices

In professional development as in youth development, we scaffold opportunities for participants to move from experiential learning to leadership, providing opportunities for voice and choice along the way. First, supervisors should look at what is happening in the program and where the organization is in its evolution of a culture of learning. Then they can build PLCs in incremental steps. A basic PLC can take place during regular staff meetings, if time is built in for discussion of staff-selected topics. Once staff are familiar with the process of collaborative learning, supervisors can identify staff interested in leading or participating in another format, such as one of those described above. A successful PLC requires supervisor support, which could include giving time on a monthly meeting agenda or structuring staff schedules to accommodate meetings with colleagues (Vance, Salvaterra, Michelsen, & Newhouse, 2016). Like creating a culture of learning, establishing an ongoing PLC is a developmental process.

From the Field

The Kitty Andersen Youth Science Center (KAYSC) is a youth program out of the Science Museum of Minnesota. In addition to its full-time regular staff, KAYSC staff include interns, project assistants, and AmeriCorps volunteers. At any given time, these positions are typically held by 10 to 25 young adults, ages 18–24. AmeriCorps positions are one year; other positions may last up to three years, depending on the role and funding. The individual goals of these short-term staff members vary: Some want to continue in youth work, some want to work for the museum, and some are interested in science careers or in entirely different fields. KAYSC is committed to their learning.

The project manager who oversees these young workers convenes them as what KAYSC calls the Leadership Cohort once a month for approximately three (paid) hours. Because these staff members work on different projects, this is the only time for them to learn as a group. Leadership Cohort learning, based on the KAYSC program model, includes leadership in using science and technology for social justice and development of youth work skills. Processes include shared skill building, networking, and community building. Robby Callahan Schrieber, KAYSC program manager, described why KAYSC has committed to creating a learning community with staff:

It is part of our core values that we are a program of community, connective and reflective experiences. Young people, interns, and staff are all here for a shared experience of constant learning and growth. We work hard to write professional development time into grants…. We hear from directors that this is a huge value to support and retain staff. The work we do does not have the greatest compensation, so we want to ensure there is the added benefit of growth. This has made our department healthier. (personal communication, April 15, 2015) JOCELYN S. WIEDOW is the network and quality coordinator at Sprockets, a citywide network that improves the quality, availability, and effectiveness of out-of-school time learning in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She completed the NIOST Afterschool Matters Fellowship in 2017 and the NorthStar Youth Worker Fellowship in 2015. She holds a master’s degree in public nonprofit administration.

Of course KAYSC also offers regular development for other staff as well. During an especially busy year, weekly cross-department staff meetings became cumbersome—but, as a learning organization, KAYSC recognized the value of gathering all staff to learn together. The supervisors therefore introduced brown-bag lunches. Each month, a different staff member presents a specific topic, often based on that person’s specialty, or teaches learning from an outside training. The lunch meetings are paid time to reinforce the idea that KAYSC values shared learning.

Peer Observations

Peer observation is a strategy that can provide learning for both the observer and the observed. Though In professional development as in youth development, we scaffold opportunities for participants to move from experiential learning to leadership, providing opportunities for voice and choice along the way. 26 Afterschool Matters, 28 Fall 2018 observations are used for performance evaluations, that is not the intent when focusing on professional development. In an organization that has built a culture of learning, staff will welcome observations, knowing the intent is development and not evaluation. Two sample peer observation practices are learning walks and use of formal assessment tools.

Learning walks enable staff to observe other staff in action during program sessions. Observers and those being observed agree in advance on the focus of the observation. The program’s goals often inform what observers look for. As they walk through other staff members’ program spaces, the observers take notes on the agreed-upon topics. These notes should be objective: What observers see, not what they think about what they see. A variety of school-day learning walk templates are available on the Internet, but another option is for staff to develop their own protocol—in itself is a collaborative learning opportunity.

Assessment tools like those reviewed by the Forum for Youth Investment (Yohalem, Wilson-Ahlstrom, Fischer, & Shinn, 2009) can help supervisors structure peer observations. Though these tools are often used by external evaluators, they also can be used for low-stakes observations as part of a continuous improvement cycle. They allow programs to measure specific staff practices including relationships, environment, engagement, social norms, skill-building opportunities, and routines or structures. Typical observations cover a full program session from start to finish. However, staff and supervisors can work together to adapt assessment tools to shorter peer observations focused on mutual learning.

- Using a clear protocol that is understood by all staff

- Identifying the focus of the observation so that it is understood by both the observer and the observed

- Taking objective notes during the observation

- Reflecting on the observation, usually with the staff member observed, either individually or in a small group

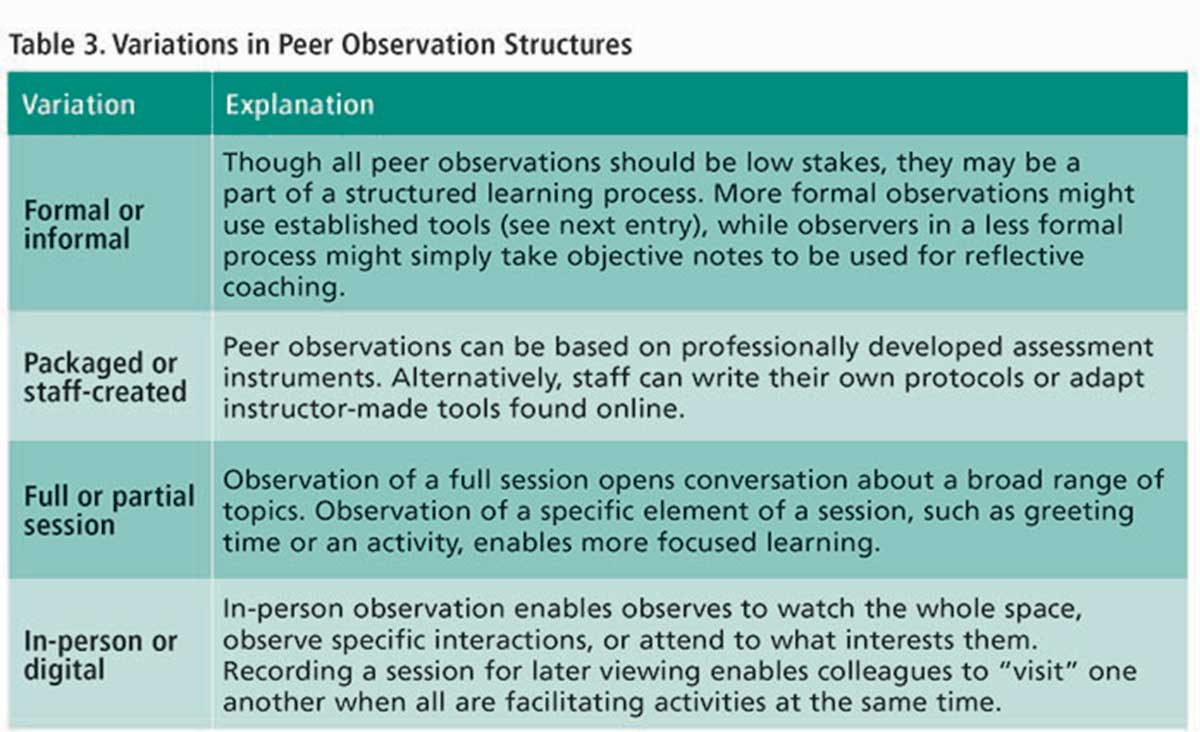

Table 3 outlines some of the possible variations in peer observation structures.

Whatever the structure, the process should include planning before and reflection after the observation. That’s where the magic happens! During the planning, staff will agree on logistics and, more importantly, on the focus of the observation. The post-observation reflection depends on the purpose of the observation. In some cases, the observation benefits the observers, who reflect after the observation on the practices they observed in relation to their own work. Other observations are primarily for the person being observed, who uses the reflection time with observers to identify practices she or he wants to improve. Observers can use coaching strategies to make reflection time fully effective. For organization-wide improvement, multiple observations provide aggregate data that determines organization-wide development needs.

Supervisor Best Practices

The role of supervisors is to determine what observation strategy best fits the staff and the program. First, they must assess the extent to which the organization has established a learning culture. Do staff trust one another and have interest in learning and growing together? This foundation is critical. Being part of a low-stakes continuous improvement cycle strengthens trust. Furthermore, buy-in develops when staff are involved in setting up the process.

Second, supervisors must consider the capacity and structure of the program or organization. A thoughtful small step is better than jumping in unprepared. Will specific staff members pilot a process, or will peer observation be implemented across the whole program from the start? Another issue is the availability of tools. Does the organization or local OST system use a formal assessment tool that the program can adopt or adapt? Would someone on the team be interested in developing a learning walk protocol? Such questions can help supervisors determine the strategy and scope of implementation.

Third, supervisors are responsible for clear communication, which is necessary to maximize the effectiveness of the process—even when the observations use less formal methods. Transparency strengthens trust and helps a learning culture grow.

Finally, supervisors must encourage reflection, in which staff members make meaning of the observation data. Besides enabling observers and staff who have been observed to have meaningful conversations about findings, supervisors should also reflect with staff on the implementation of the process.

From the Field

Flipside is Saint Paul Public School’s 21st Century Community Learning Centers program for middle school students. Each of the 10 school sites has a full-time coordinator who manages logistics and supports the instructors.

To help these instructors grow, Flipside uses learning walks, in which small teams of two or three people float among two or more programming spaces for 15 to 30 minutes. Teams may include instructors, other site coordinators, and, in established sites, youth or parent leaders. Teams begin with an orientation to the learning walk protocol: its purpose, terms, and materials. The protocol aligns with the Youth Program Quality Assessment (David P. Weikart Center for Youth Program Quality, n.d.), which is used for formal observations. The observations focus on:

- Identifying, promoting, and celebrating high-quality practices

- Reinforcing shared thinking about what quality looks like

- Creating a feedback and learning loop through shared reflection

Recognizing that each site may be in a different state of readiness, supervisors have a three-phase approach to implementing learning walks.

- Stabilizing: Coordinators complete the learning walk orientation and participate in learning walks with an experienced coordinator.

- Stability achieved: Coordinators complete a minimum of two learning walks per year, train staff to observe, and establish a data-based reflection process to engage staff.

- Stability being maintained: Sites complete monthly learning walks, engaging various stakeholders as observers. Data-based reflection is built in. Non-staff stakeholders are trained to participate in learning walks.

Sites that are new or have changed coordinators often begin at the first phase. The goal in later phases is to engage all staff and even program participants in learning walks.

Supervisors Are the Key

The role of supervisors is critical to staff learning and growth. To embed professional development in day-to-day program work, they must first examine their own practice of supervision. Then they can look at ways to meet the professional development needs of staff—during paid work time, as an expected part of regular job duties. Staff meetings that communicate day-to-day logistics are not enough. Supervisors must create and sustain a culture of learning that values continuous growth. Staff must have time and space to apply learning directly to their work.

Fortunately, OST supervisors already have the expertise they need. Youth development practices can serve as a model for professional development that engages staff in shared learning. All three strategies discussed in this paper can be effective, whether used individually or in combination. Supervisors should consider what structures are already in place in their programs for job-embedded professional development. From there, they can identify steps to strengthen what currently exists. When supervisors establish a culture of learning and strengthen job-embedded professional development, staff skills and abilities improve. As a result, staff and programs get stronger in their ability to serve program participants.

Tags: Workforce Development, Professional Development, Tools, Interventions, Outcomes, Assessment, Program Quality