Youth GO: An Approach to Gathering Youth Perspectives in Out-of-School Time Programs

By Sara T. Stacy, Ignacio D. Acevedo-Polakovich, and Jonathan Rosewood

Including youth in the development and evaluation of outof- school time (OST) programs has positive effects on youth, the organizations that serve them, and the communities in which they live (Checkoway et al., 2003). Such involvement can improve young people’s social competence (Hubbard, 2015), foster leadership and engagement (Zeller-Berkman, Muñoz-Proto, & Torre, 2013), and empower groups (Berg, Coman, & Schensul, 2009).

Including youth in the development and evaluation of outof- school time (OST) programs has positive effects on youth, the organizations that serve them, and the communities in which they live (Checkoway et al., 2003). Such involvement can improve young people’s social competence (Hubbard, 2015), foster leadership and engagement (Zeller-Berkman, Muñoz-Proto, & Torre, 2013), and empower groups (Berg, Coman, & Schensul, 2009).

Youth provide unique perspectives on their lived experiences (Checkoway & Richards-Schuster, 2004; Jacquez, Vaughn, & Wagner, 2013; Wong, Zimmerman, & Parker, 2010). Their clear insights are valuable contributions to the development and evaluation of OST programs. For example, incorporating a youth council can enhance OST program accountability and drive program improvement (Hubbard, 2015). Simply considering youth perspectives can not only improve OST service development and youth support but also increase service use and access (Kirby, Lanyon, Cronin, & Sinclair, 2003).

Despite these benefits, OST programs face challenges in incorporating youth perspectives. One is the perceptions of program staff, who may see youth as problems rather than resources (Checkoway & Richards-Schuster, 2004) or as less valuable or knowledgeable than adults (Langhout & Thomas, 2010). Resource constraints are another challenge. Many approaches to gathering youth perspectives require significant capacity, staff, time, and space (Ozer & Douglas, 2013; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2013). Program staff and administrators may not know about approaches to gathering youth perspectives that align with their resources and are easy to implement.

This article describes Youth Generate and Organize (Youth GO), a structured, developmentally appropriate approach to gathering youth perspectives designed to be implemented with the time and resources available in most OST settings. The strengths, limitations, and feasibility of Youth GO are illustrated through its implementation in an OST program to support the academic success of youth living in public housing.

Context

Students in public housing face significant obstacles to their educational success including poverty and reduced access to resources (Bradley, Corwyn, McAdoo, & Coll, 2001; Currie & Yelowitz, 2000; Newman & Harkness, 2000). Their parents sometimes report feeling marginalized from academic settings, a feeling that keeps them from being involved in their child’s education (Yoder & Lopez, 2013). Thus, students who live in public housing tend to perform worse than others on academic achievement tests and other measures of educational success (Currie & Yelowitz, 2000; Newman & Harkness, 2000).

In response to these needs, the Edgewood Village Network Center in East Lansing, Michigan, developed the Scholars Program for middle and high school students who live in the public housing complex. The Scholars Program supports the academic success, high school graduation, and college admittance of its participants in three ways.

- It responds to their current educational needs by providing supports such as homework help, tutor-mentors, and grade monitoring.

- It supports life skill development through community service, job opportunities, and professional development, among others.

- It introduces students to college culture through, for example, college tours, entrance test preparation, and summer programs.

Two part-time staff of the Edgewood Village Network Center serve as program director and assistant director to implement the program and support its capacity. A committee with representatives from the community, local organizations, and Michigan State University also supports program capacity by obtaining program funding, planning large events, and connecting the program to other resources.

Participants in the Scholars Program meet once a week for a two-hour session. During the first hour, students engage in education-related activities, such as listening to invited speakers or working with an afterschool curriculum. During the second hour, they receive individualized support, such as homework help or supplemental online learning. University students volunteer as tutor-mentors, providing individualized assistance and serving as positive role models. Community members and representatives of local organizations volunteer as speakers, lead information sessions, and provide transportation to events.

The Youth GO Approach

We developed Youth GO as an approach to gathering participant perspectives that can be implemented with the resource and staff constraints OST programs commonly face. Youth GO integrates components and principles of youth participatory action research (for example, Foster-Fishman, Law, Lichty, & Aoun, 2010; Vaughn, Jacquez, Zhao, & Lang, 2011) and participatory evaluation approaches (Chen, Weiss, Johnston Nicholson, & Girls Incorporated, 2010; London, Zimmerman, & Erbstein, 2003; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2013). Specifically, we combined processes from the group-level assessment approach, developed by Vaughn and colleagues (2011), with processes from the Youth ReACT method, developed by Foster-Fishman and colleagues (2010), along with our own knowledge of participatory processes.

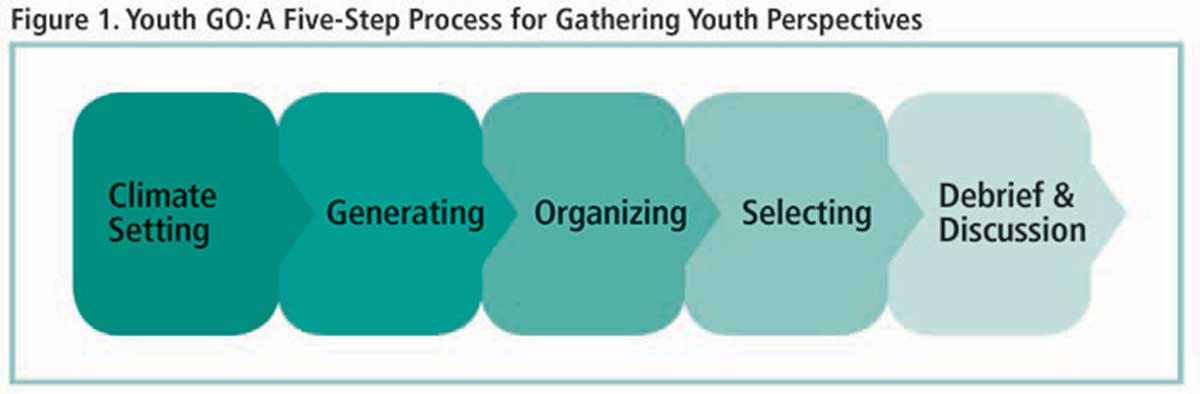

In Youth GO, groups of four to eight young people per adult facilitator articulate and organize their perspectives on target issues, such as their OST program, a set of community issues, or their own needs. The five steps are summarized in Figure 1. During Step 1, climate setting, the purpose and goals of Youth GO are introduced, and participants work with the facilitator to create group rules. During Step 2, generating, participants individually answer prompts that will inform subsequent discussion; then they discuss their answers as a group. In Step 3, organizing, participants interpret the perspectives shared during Step 2 and sort them into themes. During Step 4, selecting, participants define meaningful categories for those themes. During Step 5, debrief and discussion, the facilitator reminds participants of the purpose of the exercise, highlights the importance of participants’ perspectives, and guides a brief discussion about their experience.

To illustrate the feasibility and utility of Youth GO in OST settings, we describe two implementations in the Scholars Program. The first, more detailed example establishes the feasibility of using Youth GO and describes some of its effects. The second, briefer example provides preliminary evidence of how participants perceived the acceptability, appropriateness, and youth-friendliness of Youth GO.

First Implementation: Establishing Feasibility and Observing Organizational Change

Before implementing Youth GO, facilitators must define project goals, such as program evaluation, improvement, or development; they must also outline participant responsibilities in a way that is responsive to the strengths and developmental stage of the youth involved (Wong et al., 2010). To maximize the positive developmental effects, these components can be negotiated with youth and adults in a collaborative process (Wong et al., 2010).

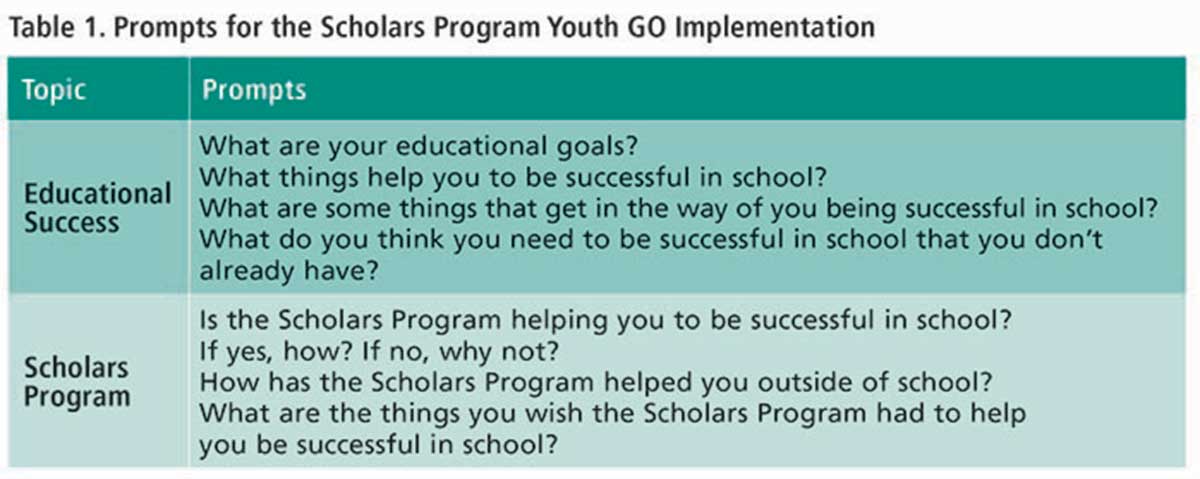

For this first implementation, Scholars Program staff contacted a Michigan State researcher to explore ways to gather the perspectives of program participants. The researcher and program staff identified the goal of the Youth GO implementation: to explore participants’ perspectives on factors that affect their educational success and on whether and how the Scholars Program contributes. The university and program staff also developed the prompts to be used in the implementation, presented as examples in Table 1. The prompts will change with each Youth GO implementation to align with the purpose and goals of that particular implementation.

To respect the structure of the Scholars Program, Youth GO was implemented during the first hour of two regular sessions for middle school participants. Steps 1 and 2 were implemented during one session, lasting about 35 minutes. Steps 3 through 5 took about 75 minutes in the second session. Because part of the exercise focused on evaluating the program, two graduate students, rather than Scholars Program staff, facilitated Youth GO. One graduate student was lead facilitator, and the other provided support such as facilitating a second small group when needed, helping individual youth with reading or writing, and making observational notes.

Eight middle school youth, grades 6 to 8, participated in this first implementation of Youth GO. All lived in Edgewood Village and regularly participated in the Scholars program.

Implementing the Youth GO Steps

Step 1, Climate Setting

Youth GO begins with group introductions, a brief presentation of purpose and goals, and the development of a community agreement. In the Scholars Program, after facilitators and participants introduced themselves, the facilitators told participants about the purpose of the Youth GO implementation: to explore and organize participants’ perspectives on how their school and the program support their education. Participants were told that this information would be used for program improvement.

Facilitators and youth then worked together to create a community agreement to guide group behavior during the rest of the process (Figure 2). The group developed six rules, which included not only courtesy guidelines such as “look at the person talking” and “don’t speak when others are” but also broader principles such as “everybody shares ideas” and “be positive.”

Step 2, Generating

Step 2, generating, uses prompts like the ones in Table 1 in a four-phase procedure:

- A prompt is revealed and read aloud to participants, who can then ask questions about it. Each prompt is on a separate piece of flip chart paper.

- Participants write their individual answers to the prompt on sticky notes or cards.

- Participants place their responses on the flip chart paper corresponding to this prompt.

- Facilitators lead a group discussion about the responses to this prompt. They may ask follow-up questions to clarify responses. For instance, in response to the prompt about what students wished the Scholars Program had to help them, one participant wrote “money.” When the facilitator followed up, the individual clarified that “money” should be used to plan more college visits. Youth can add responses that come up during the discussion.

This four-phase process is repeated for all prompts. In the Scholars Program implementation, the four phases were repeated seven times, once for each prompt (Figure 3).

Step 3, Organizing

Most participatory approaches fail to give youth a meaningful role in interpreting data (Jacquez et al., 2013). When participants are not involved in data analysis, efforts to capture their perspectives can fail to account for their unique and clear insight into their lived experiences (Checkoway & Richards-Schuster, 2004; Jacquez et al., 2013; Wong et al., 2010). To address these concerns, Step 3 of Youth GO supports youth in analyzing and interpreting the data generated during Step 2. and interpreting the data generated during Step 2.

Step 3 begins with a developmentally appropriate game, created by Foster-Fishman and colleagues (2010), to introduce data organization skills. This step can take place in the whole group or in smaller groups. In this implementation of Youth GO, students split into two groups to play this game with about four youth per facilitator. The facilitators then introduce the game:

Imagine that your team owns a new store that has a small inventory of candy. Your team buys four bins to organize the candy for the customers. You must come up with a name for each bin. The names must be clear enough so that customers who can’t see the candy still know what type of candy is inside each bin.

The groups are then given about 10 pieces of assorted candy and four small squares of paper to represent the bins. The facilitators support the students in working together to organize the candy into four categories and to create labels. Once this process is complete, participants are given a new direction:

Now imagine that two of your bins broke. Organize the candy again and come up with a name for each bin. The names must still be clear enough so that customers who can’t see the candy know what type of candy is inside each bin.

Students are then given only two squares of paper to represent the bins, so they must reorganize the candy and create new labels. After students complete this second task, facilitators guide a brief discussion about the organization exercise and how it relates to the next activity, which is to organize the responses to prompts from Step 2.

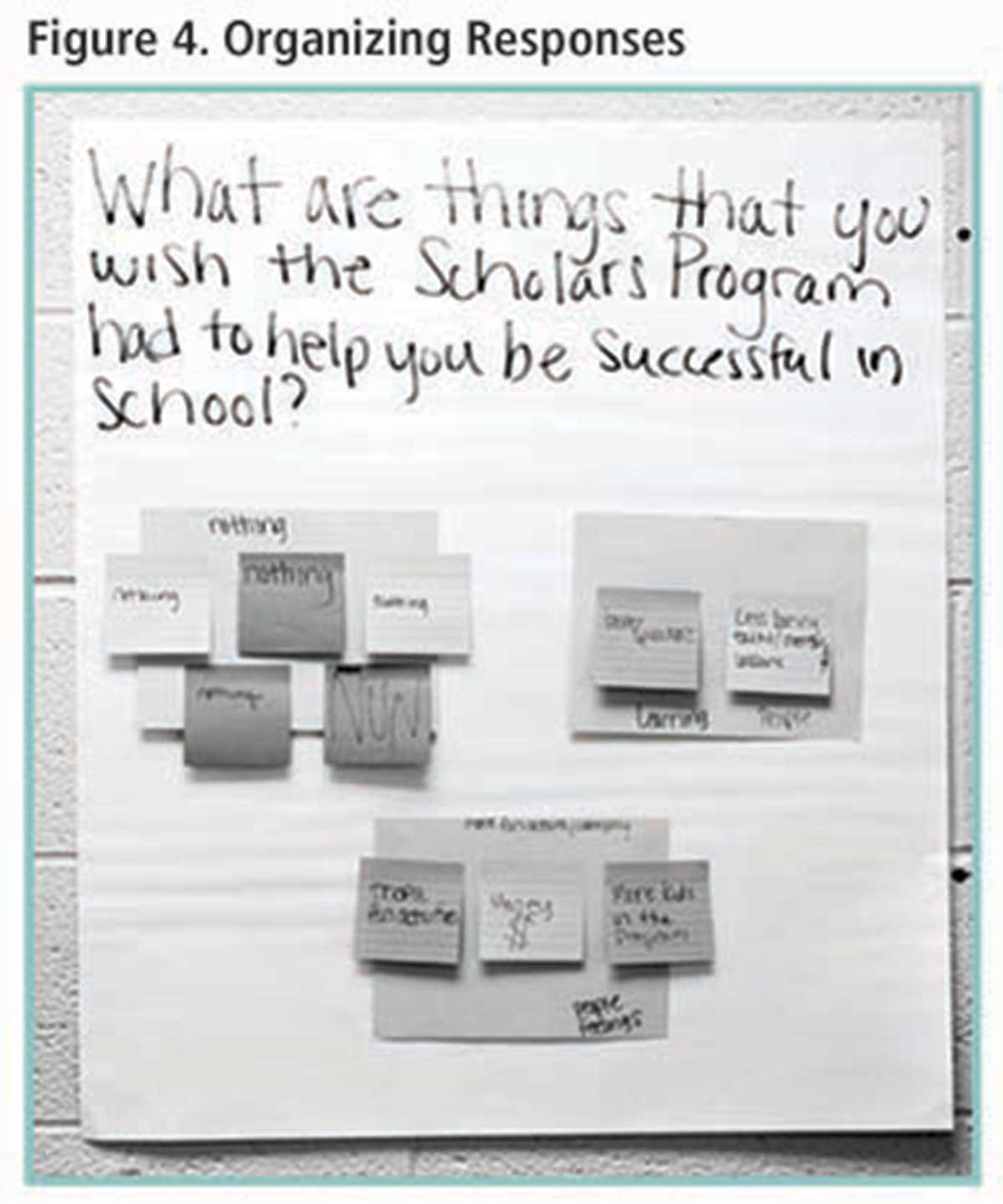

Next, facilitators support the small groups in organizing responses to the prompts. In the Scholars Program implementation, each small group was given three or four of the flip chart sheets containing prompts and responses from Step 2. Each group used the skills they had just learned to create themes for the responses to each prompt; facilitators assisted only when needed. For instance, one group was given the prompt, “What are the things you wish the Scholars Program had to help you be successful in school?” Responses included “nothing” (which occurred five times), “better speakers,” “less boring talks/lectures in lessons,” “money to visit colleges,” “more kids in the program,” “an amusement park or other fun things,” and “more fun activities.” The students organized these responses into three themes by placing the sticky notes onto sheets of colored paper (Figure 4). The students named these themes nothing, better speakers, and more fun. Each group created themes for all prompts assigned to them.

Step 4, Selecting

In Step 4, youth work in the large group to identify central categories to contain the themes created in Step 3. First, participants discuss the themes. Then they create overarching categories and examine their usefulness. Facilitators support a process in which the group discusses potential categories proposed by individuals. When group opinion on a proposed category is divided, participants vote “thumbs up” or “thumbs down.” If more than 50 percent of participants agree, the facilitators write down the category for further processing.

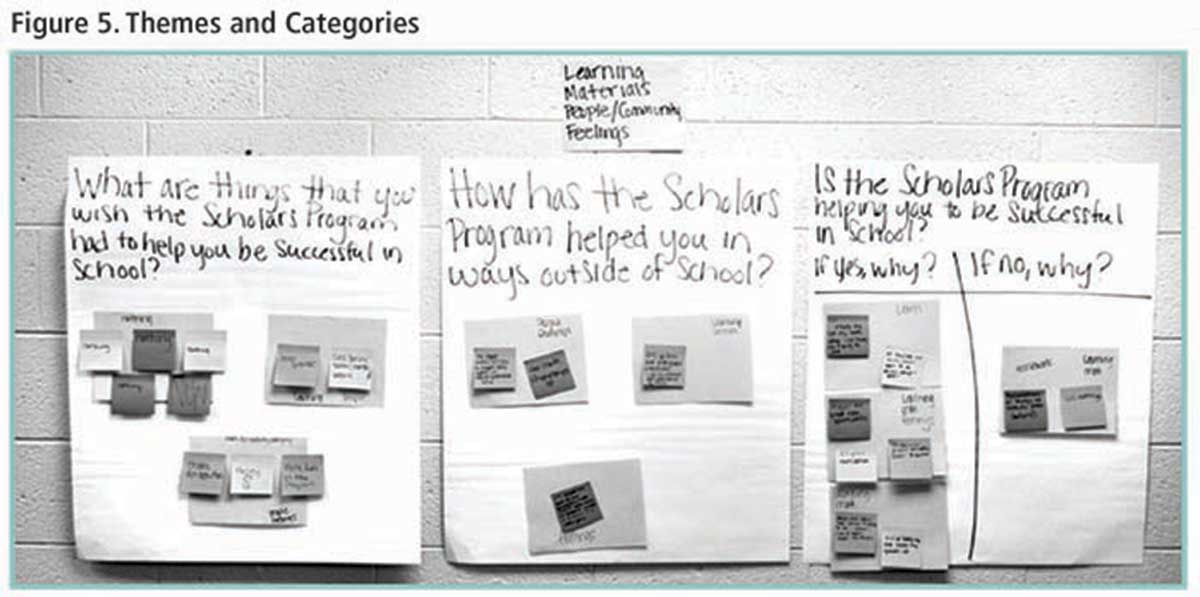

The group then determines the usefulness of the categories by checking that all categories include at least one theme and that all themes are components of at least one category. Each theme created in Step 3 is read aloud, and then participants indicate which category, if any, best classifies the theme. If they determine that the theme aligns with a category, that category is written next to that theme. A theme may have more than one category (Figure 5).

In the Scholars Program implementation, the group went through this process twice, once for the prompts on educational success and again for the prompts on the Scholars Program. For the prompts and themes related to the program itself, the group decided on three categories: learning materials, people/community, and feelings. Participants checked the validity of these categories by assigning all of the themes created in Step 3 to at least one of these categories. Collectively, the participants felt that these three categories captured the main components of the data that they generated about the Scholars Program.

Step 5, Debrief and Discussion

In Step 5, youth reflect on their experience with Youth GO. In the Scholars Program implementation, facilitators first reminded youth that this information would be used to help program leaders both to understand what makes students successful in school and to improve the program to better support participants’ needs. Then facilitators guided a group discussion about youths’ experience with the Youth GO approach. Finally, facilitators thanked participants for their time and thoughtfulness and reminded them of the value of their perspective.

Using Youth GO Results to Guide

Organizational Changes

After the Youth GO process is completed, the results must be compiled so they can be used in a way that aligns with program needs and resources. Program youth could be involved in this process, though they were not in the Scholars Program implementation. In this instance, the university researchers compiled the results into a written report. After program staff reviewed the report, they met with one of the researchers, who answered their questions and checked their understanding of the findings.

Program staff then used the report’s feedback to adapt the programming. For instance, a major finding from the Youth GO implementation was that students wanted more engaging enrichment activities; they asked for “more fun activities” and “less boring talks.” Program staff therefore implemented more enrichment activities the next year, offering, for example, bowling nights, sporting events, and community service opportunities.

Second Implementation: Examination of Youth Perspectives

After demonstrating the feasibility of implementing Youth GO and observing its beneficial effects, program and university staff planned a second implementation of Youth GO for the next program year. This implementation, conducted during summer programing in one 90-minute session, involved four Scholars Program high school youth, grades 9 through 11. A graduate student served as lead facilitator, and an undergraduate student provided additional support and took observational notes. This second implementation of Youth GO followed the same five-step process as the first implementation, using the same prompts focused on participants’ educational needs and on the supports offered by the Scholars Program (Table 1).

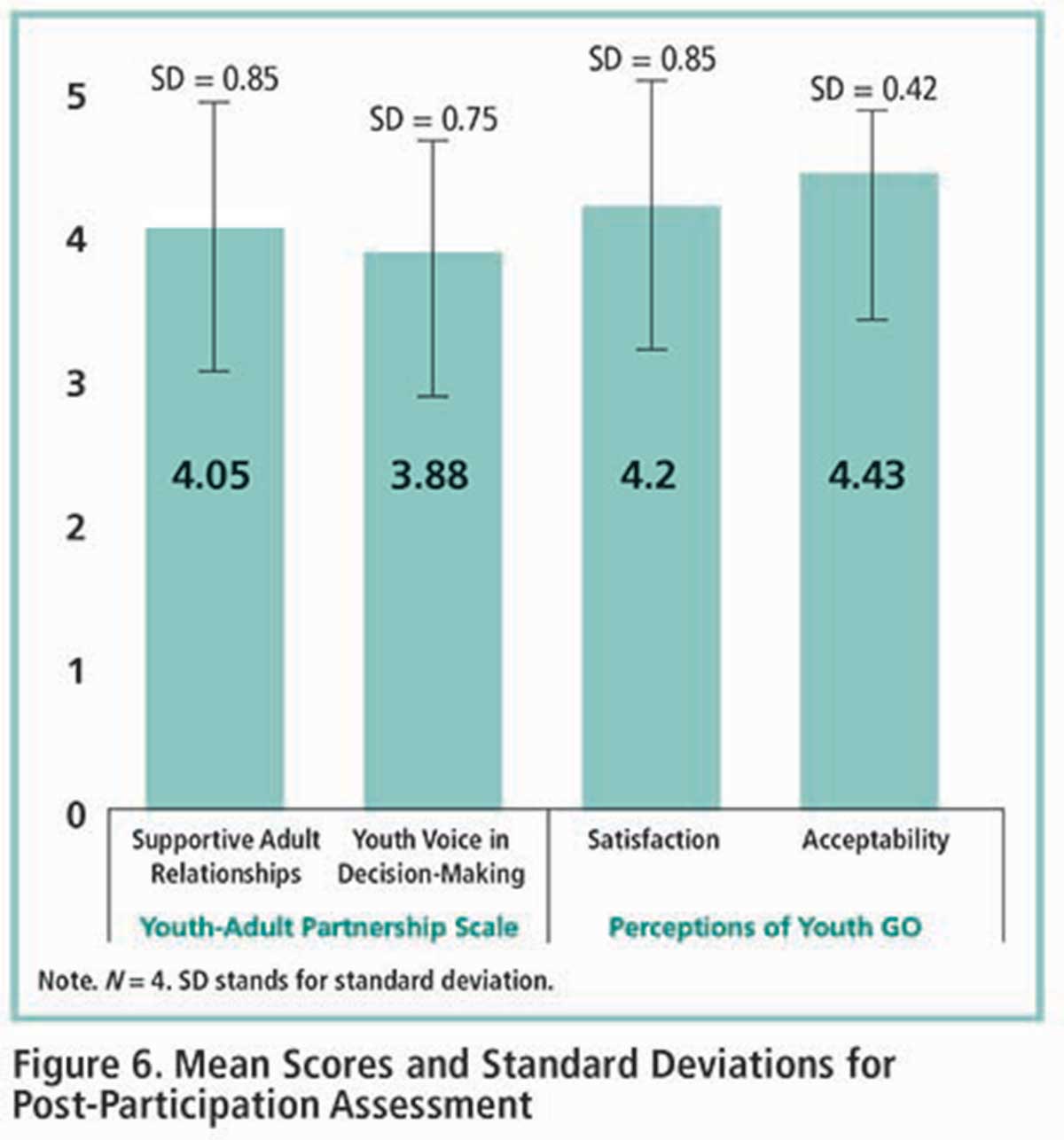

In addition to the goals of the first implementation, this implementation had a secondary objective of examining participants’ perspectives on Youth GO itself. After participating in the Youth GO process, participants completed a brief questionnaire about their experience. This questionnaire included the Youth-Adult Partnerships Scale (Zeldin, Petrokubi, & MacNeil, 2008), which contains measures of youth voice in decision-making and of supportive adult relationships. To these we added items assessing satisfaction and acceptability that we created for this project. Participants responded to all items using a Likert scale, ranked 1–5. The average responses for each scale are presented in Figure 6. Results show that this small sample of participants felt that Youth GO facilitators were supportive and that their perspective was valued within the group. They also expressed general satisfaction with the Youth GO approach and felt that it was acceptable for use with other youth their age.

Lessons Learned

The Youth GO approach to gathering youth perspectives was developed with the goal of being accessible to a broad range of OST and youth-focused programs. Incorporating principles of youth participatory action research and evaluation, it was designed to be used for multiple purposes, including needs assessments and program design or evaluation. The implementations described in this article reveal the strengths and limitations of Youth GO in meeting those goals.

Strengths

Four strengths of Youth GO are illustrated in its implementation with the Scholars Program youth. First, Youth GO requires relatively few resources of materials, time, and training. This feature is important because resource constraints often prevent the inclusion of youth perspectives (Checkoway & Richards-Schuster, 2004; Foster-Fishman et al., 2010; Ozer & Douglas, 2013; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2013). The estimated cost of all materials needed for a typical Youth GO implementation is around $55. However, OST programs may already have many, if not all, of these materials—flip chart paper, sticky notes, markers, and the like—thus resulting in little to no outright cost. In terms of time, Youth GO can be implemented in just one or two regular program sessions. In terms of staff training, many OST program staff already have the skills to facilitate a process like Youth GO.

Second, Youth GO incorporates developmentally appropriate data organization techniques for youth, as identified by Foster-Fishman and colleagues (2010). These techniques introduce youth to qualitative data analysis in an engaging manner that still encourages scientific rigor (Foster-Fishman et al., 2010). They also include youth in a process from which they are typically excluded (Jacquez et al., 2013).

Third, youth seem to find Youth GO positive and engaging. In both implementations of Youth GO, we observed participants seeming to enjoy the process. After the first implementation, participants commented that it was fun. One said, “The Scholars Program should do more things like this.” In the second implementation, participants’ responses to our brief questionnaire indicated that they both were satisfied with the approach and felt it was acceptable for other youth their age. Though the sample was small, this finding is promising. Youth engagement and enjoyment is often an indicator of program quality (Hirsch, Mekinda, & Stawicki, 2010). Engagement can enhance a program’s developmental, behavioral, relational, and academic effects (Yohalem & Wilson-Ahlstrom, 2010).

Finally, Scholars Program administrators later used the information gathered in this process for program planning and improvement. Using youth perspectives to improve programs can have positive effects both on participants (Berg et al., 2009; Hubbard, 2015; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2013) and on programs (Checkoway et al., 2003; Kirby et al., 2003).

Limitations

Some limitations to the Youth GO approach were also illustrated in its implementation with the Scholars Program. First, successful implementation of Youth GO requires experienced facilitators to lead discussions and manage the group. Effective facilitation requires quick and creative thinking and experience in handing group dynamics (Ozer, Ritterman, & Wanis, 2010; Wilson et al., 2007). In the Scholars Program implementation, graduate and undergraduate student facilitators had been trained in the Youth GO approach and had prior expertise in youth engagement programming and techniques. Though many, perhaps most, OST practitioners are skilled facilitators, those interested in further developing this skill before implementing Youth GO have many trainings, books, and videos (such as Garmston & Wellman, 2016) available to help them.

Second, the information youth generated in Youth GO was constrained by the prompts we presented and by the young people’s current understanding of the issues. For instance, students in the Scholars Program identified the main educational barriers they faced as interpersonal issues, primarily relationships with friends and with boyfriends or girlfriends. They did not discuss broader structural or systemic barriers such as poverty or racism. Young people who are presented with a different set of prompts or who participate in programs that raise awareness of systemic issues (e.g., Cammarota, 2007) are likely to provide different information.

Considerations for OST Research and Practice

Our work here suggests that Youth GO is feasible and useful in one OST setting. Our small sample of participants found the approach satisfactory and acceptable for use among youth their age. Future research could evaluate the utility of Youth GO in additional contexts and with different groups of youth. Research could also examine whether participation in Youth GO has short-term positive development effects like those found for the approaches that informed its development (Berg et al., 2009; Checkoway et al., 2003; Hubbard, 2015; Zeller-Berkman et al., 2013). Another avenue for future research is to compare Youth GO against similar approaches on relevant variables: youth outcomes such as empowerment, implementation variables including adoptability and adaptability, and program outcomes such as satisfaction and usefulness.

Before implementing Youth GO, practitioners must address three issues. First, they must establish that they have the capacity to use the information gathered in Youth GO to improve programs and services. Not using results meaningfully can disempower youth (Wong et al., 2010). Second, practitioners must determine whether they have the necessary time and staff to implement Youth GO effectively. Although Youth GO was designed to be implemented with the resources available in most OST settings, it does require skilled facilitators and sufficient time to implement the approach with integrity. Program leaders must also assess whether to bring in outside facilitators, as the Scholars Program did, to make sure that participating youth give genuine feedback. The presence of program staff could bias participants’ responses. Third, practitioners must be clear about the purpose of their Youth GO implementation and develop prompts that correspond with the purpose. Youth GO prompts can cover a wide variety of topics. The usefulness of the results is strongly influenced by the appropriateness and focus of the prompts.

Incorporating youth as partners in research and practice is an important, albeit challenging, endeavor. Youth GO is a structured, developmentally appropriate approach to such partnership that can be easily implemented in most OST settings. By facilitating meaningful consideration of youth perspectives in OST programs, Youth GO can have positive effects on youth, their programs, and their communities.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Scholars Program staff for assisting in the development and execution of this project. We also thank participating youth for providing meaningful insight on Youth GO. Finally, we wish to thank the following members of the Michigan State University Community-AID Laboratory for assisting in the implementation and documentation of the Youth GO process: Kara Beck, Katie Clements, Sandra Gomez, and Mitchell Lindstrom.

For references, see PDF

Tags: Engagement, Professional Development, Youth Development, Interventions, Outcomes, Assessment, Program Quality, Social Emotional